- Home

- Thayer Berlyn

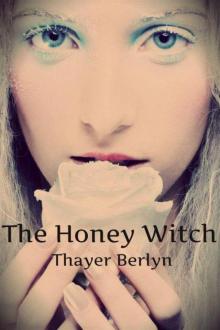

The Honey Witch (A Tale of Supernatural Suspense)

The Honey Witch (A Tale of Supernatural Suspense) Read online

The Honey Witch

by

Thayer Berlyn

Copyright 2011

All Rights Reserved.

Cover Photograph: Sergey Pristyazhnyuk

Used by permission

~*~*~

This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events and incidents are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Quoted material: William Shakespeare’s Hamlet and Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s “The Lady of Shalott” are in the Public Domain.

Fair Use: "Peanuts" comic characters referenced, in brief, created by Charles M. Schulz

~*~*~*~*~*~

The Thread

There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio,

than are dreamt of in your philosophy.

~William Shakespeare~

The journal of Dr. Ethan Broughton

Boston, Massachusetts

It had been the morning some kind of holy sprite dropped from a flowering hawthorn tree.

In the spring of 1935, Dr. Leland Broughton and two colleagues were hiking alongside the Cutler creek in search of a rare botanical, known in mountain lay term as blue poke: a delicate wild plant with a velvety sapphire blossom resembling a small pouch. When squeezed between the fingertips, the coveted bloom released a warm, purplish juice with acute antiseptic properties. Broughton discovered reference to the plant in the writings of one Dr. Charles Holt from North Carolina who, himself, described an observation of its curative powers in 1928, at the hands of a "granny" in East Tennessee.

The wonder of either testimony or madness came when the adventurous Dr. Broughton clipped the backside of a nesting pit viper with his boot heel.

Flushed with the toxin spreading from his inner thigh, Broughton waited alone for his comrades to return with aid by way of a homestead not a quarter-mile down creekside. Through a sediment of increasing delirium, he watched the gauzy figure of a strikingly pale young woman slip from her hidden perch on a nearby hawthorn branch and, with preternatural calm, move closer to assess the wound with a critical eye. She whispered, then, an unusual chant, which brushed against Broughton's ear like the swaying fronds of a wild fern. He breathed in a heavy gasp, nearly losing consciousness when the woman’s front teeth molded into the grooved fangs of the deadly serpent. He cried out in agony when those hollow spears tore deep into the injury.

Extracting the blood from the wound, with a force so voracious it seemed the very bone and sinew spattered on the earth and woodland foliage, she spewed the lethal venom in one cyclonic whirl into the humid air. The ghostly creature then slithered away, as would the snake, the sound of her body sliding through the brush until there was no sound beyond the buzzing swirl of insects and the single call of a cat bird, somewhere in the surrounding forest trees.

And this is how the good doctor’s two colleagues and three local woodsmen found him: asleep and the tourniquet removed; the wound salved with a purplish and gummy liquid.

"The Evangeline," one of the local men said. "The witch."

When pressed for an explanation, the men offered none as they silently devised a rudimentary stretcher to assist the injured man down to the old gravel road, and the back end of a dented Ford pickup truck. The departing advice, however, was clear: that it was unwise for strangers to trespass these hills; that the blue poke was an elusive bloom and not simply for the taking; that a man might live a hundred years, yet never come across one.

With this unlikely tale, came the scar Dr. Leland Broughton, my grandfather, bore until his death in 1981, a scar too deep for the initial tear of a pit viper at that water’s edge so long ago. It is the sort of yarn one files in the ledgers of family lore and I would have willingly done this, but for a similar account recorded in the diary of a Union soldier, left for dead after a twilight skirmish in West Virginia in 1863. Saved by the auspices of, “…a monstrous pale angel,” my grandfather kept a facsimile of the diary entry in his own private notebook, as perhaps a talisman of an amorphous and disoriented brotherhood whose mortal salvation came down to shared mystery.

Perhaps I might have continued to dismiss either chronicle as a mirage born from trauma, but a chance introduction at a biodiversity seminar in Chicago in 1996 stirred an old ghost. It was during that summer conference, I met a teacher and former Vista volunteer who made mention of Appalachian folk tales; a blue poke botanical and an unusual healer living on Porringer Hill in East Tennessee.

~*~

Chapter I

Wheresoever the blue purse grows,

there the Evangeline doth sow.

~Old World Proverb~

April, 1997

Porringer Hill is a ten-mile stretch of dense mountain woodland, which gradually dips into a shallow and lush valley. It was, and remains, an isolated area difficult to reach by foot and when the waters of the Cutler run high in early spring, nearly impossible by any other method.

Old world folklore tells that three nights beyond the new moon is the night of the Gypsy Moon. It was during such a night, the third since my arrival on Porringer, that I experienced a visionary dream I would only consider having been brought on by the exhaustion of travel. Standing at the threshold of a row of white oak trees, I watched as a milk-white figure twirled in the sliver of moonlight until it became but a twisting spiral of fog. And I felt a paralysis, of sorts, observing the newly formed mist rise to the top of the trees, only to then disappear, as would a vapor into the night.

The broken and hypnotic call of an owl fused with the fibril of dreamscapes, and I awoke to sense the expansion and contraction of all that, which breathed breath on the pristine hill. Plant, human and beast; each residing in curious harmony, centered on a point of unclear definition, sheltering that core, perhaps, from the corruption of civilization, itself: a civilization so foreign, that to merge one particle of the smaller into the greater would disassemble the entire functioning structure.

Three more days came and passed in a quiet repetition of watching and waiting among the inhabitants of the Four Corners hamlet, the only semblance of worldly influence on Porringer, and still the woman I arranged to interview refused an introduction to, “…the stranger who comes from God knows where.” There had been impatience, on my part: wanting answers to my research; wanting to piece together the mystery of my grandfather’s encounter. But in those uncertain days, I acquired some repose from the impulse to know the secrets of Porringer, which, I came to suspect, may have been her intention all along.

On the evening of the seventh day, I sat on the narrow doorstep of the rented cabin and considered my position in earnest, balancing expectation against increasing doubt of a dialogue which might never take place. The tender whip of an airy breeze brushed against the length of hair left neglected, just at the collar, from those bohemian days spent in the European countryside, and I swept aside a glossy winged mayfly landing on the sleeve of my shirt. Studying the narrow gap of exposed heavens between the towering treetops, I experienced an odd separation between my body and mind; of immediate time and space.

Under that glimmer of starlight, any resemblance to the carefree wanderer became strangely appropriate and the haunt of the dream resurfaced. I wondered what I’d say of it, if suddenly asked? I then found myself desiring to discuss the apparition with someone; discuss it as though it actually occurred and not simply a scene conjured in sleep.

I did not, however, wish to appear senseless among strangers.

The emergence of a recurrent trembling in my hands forced t

he quick retrieval of a prescription bottle of minor sedatives, from the travel bag hidden beneath the bed. I swallowed the chosen number of pills, aided by a single gulp from a bottle of tepid cola purchased earlier at the Four Corners mercantile.

In that moment of anticipated chemical relief, I failed to realize I was no longer alone. Aaron Westmore stood at the door.

“Dr. Broughton?”

I took another burning swallow of the warm cola, and dimly wondered if Westmore actually saw the amber container I replaced in the leather bag. With the disguised guilt of one whose secret vice rested in that nebulous realm of possible exposure, I greeted my guest with a casual smile: “Aaron.”

Aspirin, of course, I would tell him. For headaches. Chronic headaches. Aaron didn’t ask and I convinced myself he hadn’t seen.

Aaron Westmore not only prompted my interest to explore the story of Porringer Hill at the Chicago conference, but he soon became an indispensable travel guide, friend and housing assistant. In securing this simple lodging I would call home for the next several weeks, Aaron insisted that, although the two-room structure appeared as though any untoward wind might flatten its walls, the frame was of more sound construction than one would imagine. There was no plumbing to speak of in the Four Corners, but a community well just outside Pennock’s Mercantile supplied all the water one needed. After only a few days, I became quite accustomed to relying on the antiquated cistern for the pure, fresh water it gave.

“I was hoping to find you home,” said Aaron, pushing back the white Fedora hat covering his crop of dark, unruly hair. “Are you settling in well?”

I leaned lazily against the frame of the doorway. “I am, thanks.” I was, in fact, surprisingly at ease with the simplicity of quilted bed, table, chair and kerosene lamp. The rustic outhouse in back, however, would require that settling into, as would the shades of suspect arachnids hovering in darkened corners.

Aaron, apparently satisfied as to my general comfort, inhaled a deep breath of breezy air.

“Rain.”

I stepped out on the cool evening ground and surveyed the nearby trees illumined against the lantern glow inside the cabin. Indeed, a trace scent of moisture descended from a slowly forming cloud cover overhead.

“She has agreed to see you,” said Aaron.

I felt my pulse quicken. "When?"

“Anytime you choose,” Aaron replied. “I was out in the woods with some of the children, studying mushrooms, this morning when we saw her. ‘Tell the Yankee Wort Doctor, I will see him,’ were her words."

“Wort Doctor?” I inquired with some humor.

“I told her you are a plant biologist,” said Aaron, “and I’m not real certain she understands what it is you do.” He reached in his shirt pocket for a red pack of Marlboro cigarettes. “Don’t expect too much at first,” he added. “She’s not quite as…well, receiving, shall I say? as others here have been.”

“So it would seem,” I replied, absently watching Aaron tap a single cigarette against the back of his hand and again reach in his pocket for a butane lighter. The sudden flash of the gas flame projected into the trees and captured a reflective glow in the eyes of a familiar stranger.

Agitated, I impulsively grasped the lighter, preventing Aaron from extinguishing the light.

“There! Up in that tree!”

Aaron looked up. “Possum.”

I forced Aaron’s hand and held the flaming light higher.

“I’ve seen it before.”

“They’re all around here,” said Aaron, with a troubled glance at my quivering hands. He looked toward the furtive wild thing on the leafy branch and though he acknowledged the creature did, indeed, appear to be watching us in particular, he made note of its instinct to calculate any possible threat.

I concentrated on the animal for several moments and abruptly snapped the lighter shut in Aaron’s hand.

“It’s just a possum,” Aaron frowned. “And harmless. You ok?”

Still distracted, I nodded, “It startled me, I think.”

I had seen the damn thing before and each time it appeared to follow my steps, and watch me exclusively. After the unusual dream that third night, I found myself considering the most unlikely things and, one by one, rejected them all. That an animal could take on a deliberate calculation, beyond basic survival instinct, was an inventive mania.

I rubbed my brow in an effort to shake off any peculiar imaginings I feared even privately harboring. The tremor in my hands had not entirely abated and I was grateful Aaron refrained from comment.

“Do you think you might go up there tomorrow?” Aaron asked.

“What?” I replied inattentively.

“Ana,” said Aaron. “Ana Lagori. Are you going up there to see her tomorrow?”

“Yes,” I replied, somewhat guardedly. “I think I will.”

“Well, then, all’s well that ends well,” Aaron grinned, blowing out a waft of smoke between his teeth. “You’ll have to let me know how it goes. Just play up some of that New England charm and hopefully you’ll find what you’re looking for.”

I remained at the threshold of the door, long after Aaron had departed, and watched the first beaded droplets of moisture turn eventually into a steady rainfall. Assumptions seemed to vanish beneath the heady and primal scent of dampening earth. I glanced up at the tree branches and the opossum had apparently gone on its way.

Again, the lucent impression of the dream came to mind and tugged against some insistent spirit of inquiry that rose beyond the fanciful; insisting it was possible...that what I had dreamt was possible.

Or, more troubling, had actually happened.

I closed the cabin door and opened my field notebook to write under kerosene light: The woman, Ana Lagori, has finally agreed that we should meet. Observed the wretched tree rat again.

~*~

Chapter II

A slow-moving cloud passed over the crescent moon and a single flash of heat lightning lit the forest trees. I sat up in bed with a jolt. For a fleeting moment, I imagined that earlier opossum now looming on the elm branch outside the window, still staring intently through those fathomless eyes. With another flash of muted electricity, the creature disappeared. In a moment of singular unease, I shut the window and closed the faded curtains.

I awoke at mid-morning to feel the sun’s solid warmth through the thin cotton drapery, and to cringe at the ceaseless cacophony of nearby wrens.

“Hey you, Yankee Doctor!” summoned a small voice from just beyond the glass frame. I reached over and raised the window, squinting at the full onslaught of light beaming through the screen-less opening. I soon focused on Jemmy Isaak, the boy with the perennial smile and slightly magnified eyes behind the lenses of gray wire-rim glasses. Jemmy took hold of the windowsill, jumping repeatedly up and down in an abortive effort to hoist himself on the ledge.

“Whatcha doin’, Yankee Doctor?” asked Jemmy. “I had toast with jam. Grammy Nana made it from the strawberry patch before we was even out of bed. You want some?”

“Perhaps another time, Jemmy,” I told him. “But I would like coffee. Why don’t I meet you out front?”

“Ok, Yankee Doctor,” Jemmy agreed. I could hear the child’s scurrying footsteps, against the tangled brush, along the base of the outside wall.

I pulled on a pair of loose khakis and emptied a pitcher of cool water into a bowl. While I pondered the length of battery power left in the shaver, Jemmy Isaak waited dutifully outside on the front step, softly humming to himself and greeting the intermittent passerby with a piercing, "Good Morning!" When I opened the front door, buttoning my shirt, Jemmy jumped to his feet.

“Good morning!” the boy chirped. “Whatcha doin’ today? You walk with Jesus? Grammy Nana wants to know. Where ya gonna go? You goin’ up to the woods? You gonna see Possum Witch?”

Though still slightly unfocused, I was nevertheless stunned. “Possum Witch?”

“Yeah,” said Jemmy. “That’s what I call her leastw

ays. Grammy Nana too. Possum said I could.”

“That’s nice, Jemmy,” I returned sluggishly. “You want to walk to Pennock’s with me? I need that coffee.”

Jemmy smiled broadly and trotted alongside. A child of eight, he was notably thin-boned, with a sandy mop of home cut hair.

“Do you know what she calls me?” asked Jemmy.

“Who?” Both Jemmy’s chattering enthusiasm and the curious declaration of "Possum Witch," without sufficient caffeine, were too much to decipher.

“Possum Witch!” Jemmy exclaimed.

“What does she call you, then, Jemmy?"

“Mud poke.”

“Mud poke?”

“It’s a magical boy,” Jemmy instructed. “I’m a magical boy.”

“I see,” I replied.

"Were you a mud poke when you was a boy, Yankee Doctor?" asked Jemmy quite seriously.

“You can call me Ethan, if you’d like,” I smiled drowsily. “But no, I wasn’t a magical boy.”

“Too bad,” said Jemmy. He seemed to consider this for a moment and then asked: “Did you ever meet a mud poke before you met me?”

“I must say you are the first mud poke I’ve ever come across, Jemmy,” I confessed. ***

“Would you like a doughnut to go with that coffee, Dr. Broughton?” inquired the lanky Sam Pennock, from behind the counter inside his sorely outdated mercantile. “Made fresh by the wife this morning.”

“I’ll take two,” I replied, handing one to Jemmy, who accepted with a grinning: “Thanks, Yankee Doctor!”

I thumbed through the stack of days old newspapers set next to the register, and absently slid the coffee and pastry money across the dull linoleum of the counter-top.

“Any recent papers in, Mr. Pennock?”

The Honey Witch (A Tale of Supernatural Suspense)

The Honey Witch (A Tale of Supernatural Suspense)